|

If you're here hoping to attend the first meeting of Marcel's Book Club, I have good news: you're in the right place! If, on the other hand, you've wandered into Miss Marcel's Musings and wonder what's up, well this is your lucky day . . .

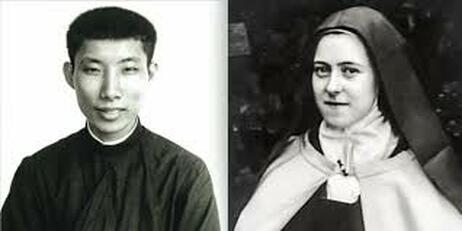

It's St. Thomas Day, for one thing - that's the feast of St. Thomas Aquinas, possibly the sweetest and most wonderful of the Doctors of the Church (though he's got plenty of competition, so it's hard to say for sure who gets the gold). And then we're starting today to talk about St. Therese (the youngest Doctor, not counting Doogie Howser, who doesn't really count since he was fictional) and her Story of a Soul. We're reading Chapter One in January, then next month it will be Chapter Two, and so on throughout this super fun year of 2019. If you've been keeping up with current events but missed this news, well that just goes to show you that the really important stuff isn't necessarily covered by the media! We chose today to start our book club (named for Marcel Van because he's the one most delighted about our year of reading St. Therese) for two reasons. First, you can only procrastinate so long in January before you wake up to find you're in February. We're pushing the envelope, what with it's being January 28th already, and we can't let this month disappear without fulfilling our promise to Marcel to talk about his favorite book, Story of a Soul. Second, I can't think of a better day to begin such Theresian talk than this propitious feast of St. Thomas Aquinas, who's been longing with all his heart to start off with us in our discussion of what turns out to be one of his favorite books, too. How do I know Story of a Soul is one of his favorites? Just an instinct related to the reaction St. Therese's autobiography brought about in so many great, holy men - I'm thinking at the moment, among others, of my friend and teacher Dr. Ron McArthur, founding president of Thomas Aquinas College and a huge fan of Therese as well as a devoted disciple of St. Thomas, but there are untold scores of others like him who couldn't say enough good things about Therese and her book. Today's the day then, and we're ready to begin, as soon as I assure you that our only rule here at MBC is you're not allowed to worry - about anything, anymore, ever, but for starters, you're especially not allowed to worry about whether you've read the assignment yet or understood or remembered it adequately. If you haven't yet read our MBC selection for January (Chapter One of Therese's Story), don't for a second worry about it. Read it when you can, and meanwhile, welcome! As to remembering it (let alone understanding it), please don't worry about that either. We live among the saints, and we'll let them share their insights, so we don't have to worry about having many (or any) ourselves! Shall we start with a prayer? Dear little Therese, big St. Thomas, and our own brother Marcel, please give little Jesus kisses for us, and Mary, and St. Joseph, and each other! Help us to know you better and learn from your books. And please help us understand what the Holy Spirit wants us to understand, to love what He wants us to love, to remember what He wants us to remember, and to laugh a lot like you do now! Amen. I was going to find a fancy prayer to officially open MBC, but who knows how long that would have delayed us? Let's get to it! Would you like a little background on how Therese came to write Story of a Soul? I think it might be helpful, especially since it will relate to the question of which version of her book you're reading, and some slight differences between editions. So here's a bit of background on our spiritual sister and her life: St. Therese was the youngest of the five girls who comprised the family of Saints Louis and Zelie Martin. There were four "little angels," two girls and two boys, who had been born, baptized and gone to heaven already by the time Marie Francoise Therese (our Therese) was born, but she was the last and beloved "Queen" of the remaining five girls who survived and who all, eventually, entered religious life. The oldest girl was Marie, and next was Pauline. This second eldest, Pauline, was the first to discern a religious vocation, and her explanations of what it meant to be a Carmelite awakened (or clarified) in Therese her own Carmelite vocation when she (Therese) was just a very little girl. Then when Therese was nine years old, Pauline entered the Carmelite monastery of cloistered nuns in the town where the Martins lived (Lisieux, France), and was given the religious name Agnes. Although Therese wouldn't have wanted Pauline to deny Jesus and was thrilled with her big sister's vocation, this departure was heartbreaking because when their mother had died five years earlier, Therese had chosen Pauline as her second mother. Now she was losing a mother again! Three years later, when Therese was twelve, her oldest sister Marie entered the same Carmel and became "Marie of the Sacred Heart." About this time the third Martin daughter, Leonie, tried out a vocation with the Poor Clares, but this didn't last long. Meanwhile, Therese was left at home with Papa and her inseparable closest-in-age and dearest friend, her sister Celine who was 3 years older than she. Therese entered the Carmel shortly after her 15th birthday, and Celine entered six and a half years later, after the death of their father, Louis. This meant four of the five Martin sisters (and later their cousin Marie Guerin) were in the Lisieux Carmel. The fifth sister, Leonie, eventually found her resting place as a religious at the Visitation in Caen, France. Thus all the Martin girls because nuns. One night in the winter of 1894, when Therese was 21 and had been a Carmelite for 6 years, the first three to enter the Carmel - Pauline (now Mother Agnes, the prioress), Marie of the Sacred Heart, and Therese - were sharing a rare moment of leisure and conversation together, talking over childhood memories. Marie told Therese, "You should write these stories down!" and Therese laughed at her. She had no intention of doing such a thing, but Marie, sly dog, turned to Mother Agnes (Pauline) and said, "Tell her she has to write, under obedience!" Luckily for us, Mother Agnes "obeyed" her older sister Marie! She told Therese, "Yes, under obedience, write for me your childhood memories." Therese, very obedient religious that she was, had no choice. She began writing in January 1895 and finished what's come to be called "Manuscript A" by the next January, in time to give it to her sister Pauline/Mother Agnes as a name day gift on January 21, 1896, feast of St. Agnes. A few months later, in April of 1896, the first symptoms of Therese's illness began to show themselves. Thus in September of 1896, Marie of the Sacred Heart, aware they might not have their amazing little sister around for too much longer, asked Therese to write something about her "Little Way" during her (Therese's) annual retreat. Therese, out of love, wrote a letter to Marie to introduce a longer letter she wrote to Jesus about all the graces He'd been giving her. These writings (again requested by Marie of the Sacred Heart, God bless her!) became known as Manuscript B. The following spring, Mother Agnes (retaining the title "Mother" as was the custom, but no longer the prioress) asked the current prioress, Mother Marie de Gonzague, to ask Therese to write down her convent memories, and thus "complete" her autobiography. Mother Marie de Gonzague agreed and Therese, again under obedience, wrote what is now called Manuscript C. Mother Marie de Gonzague also gave Mother Agnes (Pauline) permission to spend extra time with Therese in the infirmary, and so from April 6 until Therese's entrance into eternal life on September 30, 1897, Mother Agnes, Marie of the Sacred Heart, and Celine (now Sister Genevieve) were careful to write down everything St. Therese said to them - which sayings were later selectively compiled in various editions, and are currently available in their fullness, known in English as Therese's "Last Conversations." Among the many wonderful things that she said in those conversations, Therese, beginning to foresee what God had in store for her as a posthumous mission (i.e. the work she begged him to be allowed to do in Heaven, "coming down" to us on earth to teach us of His love and how to love Him in return, showering roses upon us, etc.), gave Mother Agnes carte blanche over her little writings. Thus Mother Agnes was the one to prepare the early editions of Story of a Soul, which began as the circular obituary customarily sent to the other Carmels when a Carmelite nun dies. Only in Therese's case, the circular was longer than usual, and more world changing than usual! Mother Marie de Gonzague was happy to have Mother Agnes prepare the manuscript, but required that all 3 parts (the childhood memories written for Mother Agnes, the letter(s) written for Marie, and the final bit written for herself) be addressed to her. Mother Agnes was editing out some things that might offend those still living (Therese having the gift of complete honesty and transparency!), changing little words here and there, rearranging parts for ease of reading, and so on, so this request was no problem. Later, when the process for Therese's beatification began and the Bishop was gathering her writings, the Church intervened and requested (and required) Mother Agnes to re-address the parts of Story of a Soul to their proper and original recipients. These early editions, touched up, organized, and edited by Mother Agnes, were the masterpieces that went out into the world and began the shower of roses, the avalanche of miracles that St. Therese promised and has become known for. I can't help but think, as many others before me and most especially Therese has, that Mother Agnes was the perfect person for that editing role and did a marvelously inspired job! Those first editions also contained a miscellany of Therese's letters, poetry, last conversations, and counsels to her novices, as well as (beginning only a few years after her entrance to eternal life) a selection of her "shower of roses" - the favors already granted by her, written up by the recipients and witnesses, and sent to the Lisieux Carmel from all over the world! There were translations into nearly every known language, beginning almost immediately after the first printing of 2,000 copies in September of 1898, one year after Therese's death. By the late 1940's, however, the Church and the world were becoming anxious to have Therese's writings just as they came from her pen (and pencil, at the end, when she was too weak to use a pen). The Master General of the Order (Fr. Marie-Eugene of the Child Jesus, whose vocation was inspired by his reading of Story of a Soul around the time of World War I, before Therese was even beatified, and who is now himself a Blessed) requested of Mother Agnes that the Carmel provide the original manuscripts. Mother Agnes, at this time near 90 and still prioress (she had been made so in 1936 by Pope Pius XII "until death"), having worked on Therese's mission alongside Marie of the Sacred Heart and Sister Genevieve (Celine) for decades, asked if, pretty please, the Order and the Church could wait until she died, and then give this new project to Celine. Holy Mother Church mercifully consented, and so it was under Celine's loving eyes (also old by now!) that in 1956 the good Father Francoise de Sainte Marie brought out, at last, the Autobiographical Manuscripts in their original form. Like many critical editions, they weren't entirely what we'd call reader friendly, but slowly and surely, translators made them available in various languages in much more reader friendly, but still wholly authentic-to-the-original editions. For English speakers, the definitive (at least for now) translation was given to us in the mid-1970's (I love when I can point to really great moments in the '70's; it makes me feel like Abraham finding a good man to save old S & G). The translator: Fr. John Clarke, O.C.D. (a very balanced man who was a Discalced Carmelite friar!). The publisher: ICS, short for Institute of Carmelite Studies. Interestingly, ICS came into existence as a publisher when the Washington Province of Discalced Carmelites needed to keep the Complete Works (all in one volume) of St. John of the Cross in print. When, following St. John of the Cross' book, they then published Fr. Clarke's translation of Story of a Soul, it instantly became, and has remained, their bestseller, allowing them the stability to continue to publish the original writings of many other great Carmelite Saints, Blesseds, and holy ones. Fr. Clarke's translation is now accepted as the standard throughout the English-speaking world. On my shelves I have several copies of Story of a Soul. They are all favorites. My go-to edition is Fr. Clarke's put out by ICS. My favorite as a complete book is "The Green Book" (as I affectionately call it), an English translation of an early edition of Story of a Soul which includes (as the Carmel's early editions did) assorted other writings by Therese, all translated by a Scottish priest, Fr. Thomas Taylor, and published by him in several succeeding editions from 1912 to 1926. Then there's the version that first hooked me in 1985 or so, the one translated by John Beevers, published by Doubleday/Image in a small turquoise edition in 1957, and kept in print in that format for many years. My point? If you have Fr. John Clarke's ICS edition, that's terrific. I think it's the best one, and the one I'm reading this year. If you have another edition, that's good too! If you need to get a copy of Story of a Soul, I suggest starting with Fr. Clarke's translation, which you can order directly from the Institute of Carmelite Studies, or on kindle from amazon. But really, whether your translation, edition, and copy of Story of a Soul is old or new, it will be a life changer! If you're reading along month by month and find me referring to things you haven't read in that month's chapter, chalk it up to using a different edition (if you are) or my idiocy (another likely cause)! But now, without further ado, our first order of business is to give St. Thomas the floor, because he's been waiting a while, his feast is almost over even on my far left coast, and I'd hate to make him wait till tomorrow. Due to my Marcellian memory, I can't for the life of me remember where I came across a reference to this passage he's offering us from the Summa, but come across it I did, sometime between Christmas and now, and given how eager I've been to share it with you, we can only imagine how thrilled St. Thomas is (he who loves the Truth even more than I do, though I'm working on catching up). This passage comes from the Summa Theologiae (or Theologica, as it's also called), Secunda Secundae (that's the second part of the second part), Q.83, a.11 (question 83, article 11). The whole question, which is broken down into 17 articles, is on prayer. Article 11 is titled, "Whether the Saints in Heaven pray for us," and the good news is that yes, they definitely do. (Didn't want you to spend even a nanosecond worrying about that one! And thanks again to the forgotten author whose book called my attention to a passage that I otherwise never would have seen.) As is typical in the Summa, St. Thomas starts this article with objections (in this case five of them), then presents a "Sed Contra" or a kind of "contrary to those objectors' opinions" in which he quotes an authority for the true answer, then the "corpus" or body of the article (the gist of the thing, the real answer with an argument to explain it), and then replies to the objections. Our interest today is in the fourth objection and St. Thomas' really heart-lifting reply. Ready? Objection 4: If the saints in heaven pray for us, the prayers of the higher saints would be more efficacious; and so we ought not to implore the help of the lower saints' prayers but only those of the higher saints. And then here is St. Thomas' reply to this objection: "It is God's will that inferior beings should be helped by all those that are above them, wherefore we ought to pray not only to the higher but also to the lower saints; else we should have to implore the mercy of God alone. Nevertheless it happens sometimes that prayers addressed to a saint of lower degree are more efficacious, either because he is implored with greater devotion, or because God wishes to make known his sanctity." Well how do you like that? Here's one of the greatest teachers in the Church, possibly one of the greatest saints, recommending the little saints to us as our intercessors. I think it's nothing short of marvelous! I take it as the Angelic Doctor's endorsement of our devotion to little Therese and her even littler brother, Marcel Van. And it also just so happens to fit perfectly with the opening pages of St. Therese's Story of a Soul, because there she asks the question why God would even bother making little saints. And it's there, in those first pages, that Marcel's gratitude and devotion to her began, because she happened to be asking the very question that had been plaguing him when he, all unsuspecting and even resisting, opened her book and found the answer to his troubles one evening in October of 1946, 51 years after she wrote her solution. Marcel had been filled with the desire to become a saint, but he only knew, so far. of the great saints, so he naturally thought he didn't fit the bill. In his own words, from his Autobiography (564): "The good God undoubtedly must understand me. I loved Him, and I wished to prove my love in any way, be it even with a smile or a mouthful of good rice. I hardly liked the discipline [this was an ascetical practice of hitting oneself with a type of scourge to imitate Christ's scourging at the pillar], which always frightened me, but when one loves, is it necessary to give oneself the discipline? People normally get more pleasure from a simple glance of love than from a thousand presents which may be offered to them. That is why I always remained undecided, not daring of myself to be the last in the world to become a saint, in spite of all the love I had for God. That's how it was. God brought the reply to this thorny question to me." Struggling between his love for God (and thus desire to be a saint) and his recognition of his littleness (he was so unlike the great saints he'd read about), 14 year old Marcel feared he was being presumptuous. Agonizing over this inner drama one night, Marcel turned the whole problem over to Mary and left the chapel for study hall. Having done his homework, he was free to choose a saint's book to read. He'd read the ones that interested him, so again turning to Our Lady, he asked her to choose for him, then randomly, with eyes closed, picked a book. To his disappointment, it was Story of a Soul. No pictures, and he was sure it was about another unreachable, inimitable, totally-unlike-him Saint. But he'd asked for Mary's help and now he felt obliged to read the book she'd chosen for him, so he opened it, began reading the chapter we're reading this month, and fell in love! For there, straight out of the chute, Therese posed and answered his question. And believe it or not, you've got an extra grace period to read those opening pages if you haven't yet! Because if I don't post this soon, I will have already broken my promise that we'd start today (unless you're in Hawaii, and I doubt you are because I haven't heard from anyone in Hawaii!). Tomorrow, then, we'll dive into Chapter One itself, and see how Therese captures our hearts from the get-go. It won't be until nearly the end of the year and the end of Manuscript C that we'll find our signature prayer in our monthly reading, but no need to wait until November to pray that we (a very inclusive we!) make it into the loving embrace of our darling little Jesus, so let's conclude St. Thomas' beautiful day together by praying with him to Our Lord: Draw me, we will run! As to our January MBC - to be continued . . . Comments are closed.

|

Miss MarcelI've written books and articles and even a novel. Now it's time to try a blog! For more about me personally, go to the home page and you'll get the whole scoop! If you want to send me an email, feel free to click "Contact Me" below. To receive new posts, enter your email and click "Subscribe" below. More MarcelArchives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed